In June 2022, Heather McCauley from Reform Scotland published a report “Taxing Times: Why Scotland needs new, more and better taxes“. As she was unable to contribute to a Futures Forum event with the Scottish Parliament’s Finance and Public Administration Committee on the future for Scotland’s tax system in November 2022, we invited Reform Scotland to contribute a blog instead.

In this piece, Reform Scotland’s Alison Payne outlines key points from Heather’s report and reflects on developments since the publication.

A fiscal challenge

It seems impossible to overestimate the scale of the fiscal challenge facing the Scottish Government. Huge savings need to be found while at the same time demand is increasing on our public services. Individuals are facing a cost of living crisis; energy prices are rising; and inflation is taking hold. It is the perfect storm with no obvious escape.

Unfortunately, the longer term brings additional challenges. By 2045, it is estimated that Scotland’s population will have reduced by 1.5% while the UK’s as a whole will be 5.8% larger. Scotland’s population of over 76’s will be up by more than two-thirds, while the population of those in their 30s, 40s and 50s will be static, and the population of under 30s will fall by 16%.

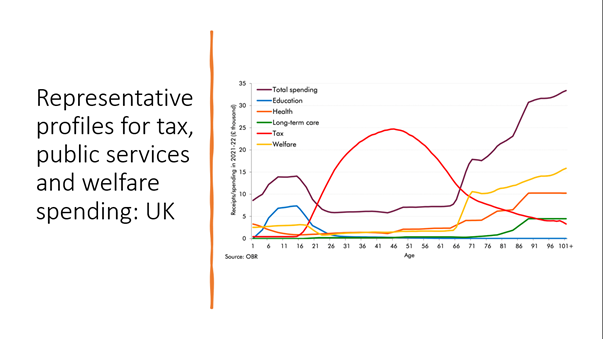

This will have significant implications for tax raising, as well as for government spending. While it is obviously a good thing that we are living longer, the graph below illustrates the revenue problem it creates if the current tax structure is retained. Under our current tax arrangements, working age people are on average are net contributors to state finances, while those over pension age cost the state more, particularly due to the state pension and health care.

Health and care already account for nearly half of devolved expenditure. Although health spending is set to increase over the course of the review period, the Fraser of Allander Institute has questioned whether that increase is enough to meet the challenges ahead. [1]

The stark dilemmas facing Scotland were laid bare in one afternoon recently at Holyrood. John Swinney’s announcement of £615 million in budget cuts, including “reprioritising of spend within health and social care” was followed by a debate highlighting the financial uncertainty around the proposed National Care Service.

The full package of social care reforms set out by Independent Review of Adult Social Care in Scotland was estimated as costing £660m per year, increasing to £1.2bn if wages were raised to the Living Wage.

At least £660m per year required to implement much-needed social care reform.

But £615m spending cuts needing to be found.

How can we fix social care in such circumstances? Indeed, how can any much needed public service reform be implemented?

Too often the debate then turns to Income Tax. Reform Scotland believes that the Scottish government is currently overly reliant on non-savings, non-dividend [NSND] income tax, which accounts for 70% of its tax revenue and leaves policy makers without the broad basket of taxes they need. It is also only just over a year ago that the SNP stood for election promising to ‘freeze income tax rates and bands’. [2]

Fiddling at the edges of one tax, a tax we are overly reliant on, cannot provide all the answers.

Instead, innovative and new ways to increase revenue will need to be considered.

New, more and better taxes

Reform Scotland recently published ‘Taxing Times: Why Scotland needs new, more and better taxes’ [3] by international public policy expert Heather McCauley. The report argues that Scotland requires a fundamental rethink of tax structures – the balance across income, consumption and wealth taxation, the extent of taxation, and the scope for Scotland to establish new tax bases.

The report highlights that too often public debate tends to focus on very specific tax choices – what an individual tax rate should be or whether a group or activity should receive a relief or exemption – in isolation from the wider tax system and its impact as a whole. Instead, McCauley argues that tax policy needs to be considered ‘in the round’ – it is the combined effect, including the distribution of cash transfers and public goods, not the progressivity of each tax individually, that matters for outcomes.

For example, if a less progressive tax is efficient, it can raise more revenue that can then be redistributed or used to reduce tax rates to achieve greater progressivity overall.

International comparisons suggest that there is no one optimal way to raise revenue. Countries vary significantly in their levels of tax and the mix of taxes imposed, and there are different ways to achieve quite similar levels of redistribution. In general, high-spend countries are also high-tax countries, but countries can raise significant revenues with lower tax rates if their taxes have a very wide base and few exemptions.

However, while lessons can be learned from other countries, it is important to also consider the context within which Scotland operates. Scotland has fewer top rate tax-payers than the UK as a whole and our close proximity to the rest of the UK means that there is a risk of tax flight, whether we are independent or not.

As a result, McCauley recommends that attention should focus on less mobile factors – particularly immobile wealth. The report notes “Taxes on the ownership of wealth are relatively economically efficient, help encourage positive wealth creation rather than “passive” wealth accumulation and are needed if a country wants to reduce (or prevent the further increase of) wealth inequalities. If they result in personal or capital flight they will tend to lead to a reduction in values which, in many cases, would improve affordability for Scottish residents.”

In the UK, wealth has increased from around three times national income in the 1970s to more than seven times in 2020, yet that growth has not been accompanied by increases in tax revenues. The amount of tax collected has remained almost flat, below 4% of GDP.

The Resolution Foundation has estimated that a person could inherit £1 million from their parents and pay no tax while someone working 40 hours a week on the National Living Wage from age 18 to 70 would only earn £753,000 in their lifetime and pay almost £100,000 in tax.

There are arguments for introducing a wealth tax at a UK level, but it could also be considered now in Scotland under the devolved powers. These important powers to create new taxes already exist at Holyrood but have yet to be properly tested. There is scope to consider different ways to tax wealth under these provisions.

Empowering local authorities

Tax reform is also urgently required at a local level. This has been acknowledged before.

For example, in 2002, a Holyrood inquiry into local government finance called for more tax powers to be devolved to councils, so enabling them to raise closer to 50% of their income.

Again in 2014, the Local Government Committee’s review called for a wider range of powers and taxes to be devolved.

Despite this cross-party agreement on the need to devolve more tax powers, nothing has actually changed.

There has been no review of the capabilities or structures of local government. Indeed, if anything, more power has been reserved to Holyrood.

Reform Scotland believes that in addition to a fundamental review of taxation, there needs to be a recalibrated balance of powers between Holyrood and local government, enabling councils to raise more of the money they spend, and improving accountability and transparency. And that requires devolution of specific powers, not just vague agreements in principle.

To begin with, local authorities should have complete control over local tax – including the rates, bands, reliefs and indeed form of the tax. This would allow individual councils, should they choose, to retain, reform or replace council tax with another form of local taxation, including different forms of wealth taxation. Crucially, this would be a decision about a local tax made by a local authority for its local area, taking into account local circumstances and priorities.

A tax system fit for the 21st century

McCauley notes in her report that many other countries have set up independent expert commissions to undertake ‘root and branch’ reviews of their tax systems every five or ten years, while retaining democratic oversight of decision making. A commission of this kind, perhaps chaired by an organisation such as the OECD, which has carried out previous reviews for the Scottish Government in the area of education, could be a good starting point for Scotland to developing a distinct tax system that is fit for the 21st century.

References

[1] First Spending Review in a decade provides welcome insight on Government priorities, and highlights scale of challenge facing public services | FAI (fraserofallander.org)

[2] SNP Manifesto 2021 by HinksBrandwise – Issuu

[3] Taxing Times: Why Scotland needs new, more and better taxes – Reform Scotland

Alison Payne

Alison Payne joined Reform Scotland in 2008 and is currently. After graduating from Edinburgh University with a degree in Economics and Politics in 2001, Alison spent four years as Head of Research for the Scottish Conservatives, later becoming Political Adviser to the then leader, Annabel Goldie MSP.

Before joining Reform Scotland Alison was a senior account manager with PPS, which provides communications and consultation advice to the property and development industry. She also spent 10 years as a Girl Guide leader and continues to help as and when she can.

Alison lives in Edinburgh with her two children and is a widow following the death of her husband from cancer in November 2015.

Scotland’s Futures Forum exists to encourage debate on Scotland’s long-term future, and we aim to share a range of perspectives. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the Futures Forum’s views.